What do we DO all day?

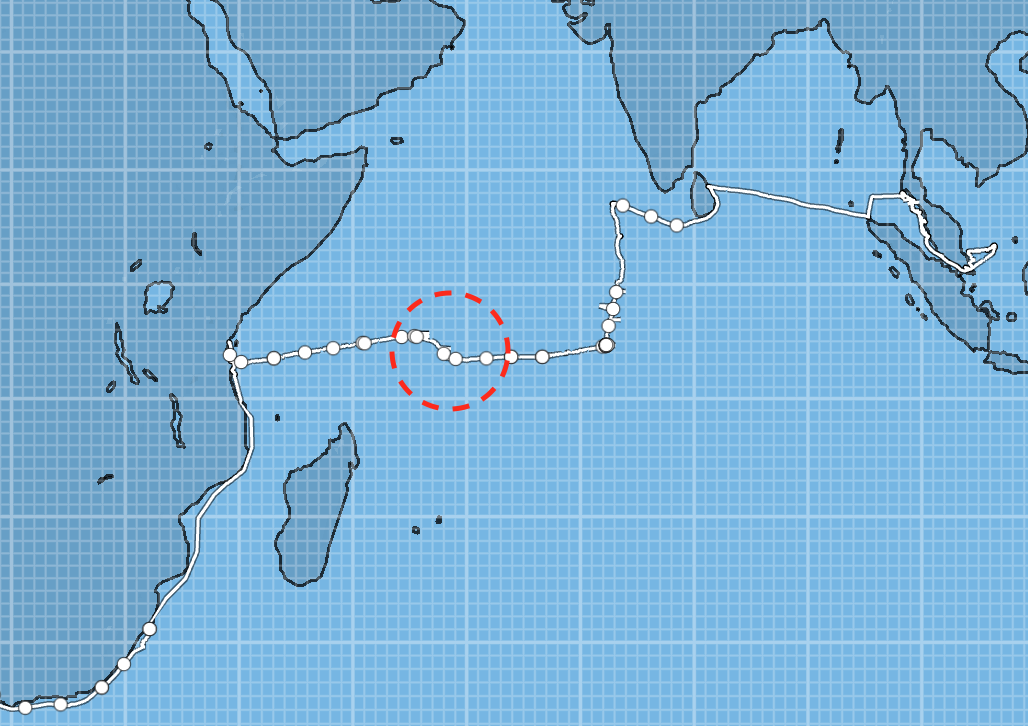

Chagos to Seychelles - Day 4

Date: Friday 7th August 2020

Local time: 15:00

Time Since Departure: 78 hours

Actual Speed: 7.1 knots

Average Speed for trip: 6.5 knots

Max Speed for trip: 11.5 knots

Distance Travelled so far: 505.7 miles

Distance to Destination: 575.4 miles

Time to destination: 81 hours

ETA: Monday 10th August, 8pm

Life on board has returned to boring old normal, I’m delighted to say.

The autopilots are behaving themselves, and we’re back to using the primary one, which means we can resume sleeping in our own cabin, rather than on the floor.

The weather has calmed down significantly, and in fact is exactly as forecast – sunny, with 15-20 knots of wind on the beam or just behind, along with a steady 2 metre swell whose long period means the boat is rocking much more gently.

We’re very close to Erie Spirit – they left 2 hours ahead of us and had already built a 13 mile lead by the time we exited the lagoon. Now, 4 days later, they’re just 15 miles ahead, remarkably both yachts sailing at almost identical speeds. That means we can see each other on the AIS, and talk on VHF, which is always nice.

Sonrisa, with a slightly smaller boat, are just a tad slower, and so over the 4 days have fallen around 60 miles behind. But when the winds die away in the next few days, we expect them to close the gap to Steely – she’s no fan of the light stuff.

And after a bit too much drama and excitement in the first two days, it’s nice to be back to the usual passage routines.

We operate a 4 hour on / 4 hour off watch system, as follows:

Jen: 9am – 1pm, 5pm – 9pm, 1am – 5am

Pete: 1pm - 5pm, 9pm – 1am, 5am – 9pm

There any many different ways to structure watch systems on a 2 person boat, but this works well for us.

We overlap at watch handovers for 5 minutes or so, and will eat lunch and dinner together. When the conditions are calm like now, we’ll typically enjoy a single beer at sunset together. Other than that, it’s a solitary, somewhat boring life.

Keeping watch on Steely is pretty straightforward. I usually sit in one corner of the cockpit, on the downwind side so gravity is pulling me into the seat, rather than having to fight to stay there. From my snug corner, I have our multi function display oriented towards me, and within finger tip reach.

On there, I’m constantly monitoring our position, the chart, the wind strength and direction, our performance, RADAR and AIS for other vessels, and the radio is nearby to speak to the very occasional passing vessel. Every 10-15 minutes or so, I’ll stand up and have a good look around in all directions. I’ll check the sails for visual signs of wear and tear, and look around the various deck fixtures to make sure there’s no obvious problems.

While on my feet, I’m also checking the weather, prevailing conditions, and if there is anything else visible. But when you’re this far out to sea, there never is… just miles and miles of rolling swell.

At the height of the bad weather a couple of days ago, I spotted a tanker on our AIS system about 30 miles away on a collision course with us, which is remarkable given how vast this stretch of ocean is.

Since his AIS broadcasts more powerfully than ours, I could see him before he could see me.

My computer was calculating in real time how close we’d get in 60 minutes when we were due to pass each other , and at one point it said less than 100m. Given that he was over 300 m long, that was WAY too close, especially given that there was a storm blowing. And since he was coming at right angles to us, that meant that avoiding each other meant a little bit more than the usual trick when you’re on a collision course where both boats turn a few degrees to starboard.

I waited until he was about 10 miles away, and then called him up to make sure he’d seen me and to discuss the situation. Commercial vessel captains (or their radio operators) are unfailingly polite, and always pleased to hear from us to discuss situations proactively.

Although technically I had right of way as a sailboat, the convention is that we keep out of the big guys’ way. It makes sense – they’ve got a job to do, we’re just out here having fun. Plus changing course on our tiny boat is generally much easier than it is on a massive supertanker.

However, on this occasion, I let him know that I had limited maneuverability as a result of the weather and the fact that we were sailing downwind, and asked him to alter course and to keep at least a mile away. He was happy to comply, and asked if I’d prefer him to pass in front or behind. We agreed he’d pass in front, and I watched him alter course on the computer.

10 minutes later, he called me back again to say that he could see that my speed was changing a lot as the wind gusted, and he was no longer comfortable that he would pass clear ahead. He asked for my agreement that he would instead pass behind me, and he then dialled in a 20 degree course shift. He passed just over 1 mile astern of us. Throughout this entire period, I never saw him once – the rain, swell and winddrift meant that visibility was down to less than a quarter of a mile.

Typically, I’ll go down below once per hour to record the log – this is both a legal requirement and can provide material safety benefit. I’ll write down our position and various other pieces of data including prevailing weather conditions, currents and any observations about the boat. In the event that we lose our electronics (which can easily happen through lightning strike or electrical malfunction), we can seamlessly move to our backup paper charts and know exactly where we are to the last hour.

While down below, I’ll monitor our battery status, check the bilges and perform some basic engine checks if they happen to be running. If the fridge or generator are in use, I’ll be checking them too.

Through the watch, I’m constantly using all of my 5 senses to spot and diagnose potential small issues before they become bigger.

Sight is obvious, but sound and smell are almost as important and used just as often. Although we read while we’re on watch, we have a rule where we are not allowed to watch movies as they’re too immersive. We can listen to music, but only with one ear piece – sound is just too important as you can hear problems with engine or generator, hear large waves coming, or unusual noises from the rigging etc. All of these are real examples where we’d have missed small problems and seen them become much bigger if we had not been paying attention.

Smell is important too – we have found diesel leaks and small electrical issues by smell alone in the past. Taste and touch play a role too – if you find water in the bilge, a common test is to taste it. Fresh water is good (that’s just a leak in your tank), salt not so good, as water is getting in from outside. And we use touch to monitor the temperature of various bits of equipment to ensure they are running correctly.

But although we’re constantly monitoring all of these pieces of data, the truth is that not much changes from minute to minute, or hour to hour. So you have a lot of time for reading, writing, playing games on your phone, or sending emails on the satphone. Oh yeah, and staring at the sun rise, the sunset, or the rolling miles of ocean.

You’ll notice that I haven’t yet mentioned any actual sailing of the boat. That’s because we hardly do a thing. The autopilot handles the steering (when it’s behaving itself), and the sails, once set, rarely need adjusting when the weather is settled. Occasionally we might put all or some of one sail away to accommodate an increase in wind, or vice versa if the wind is getting lighter – that usually takes 3 minutes, and we time it for a watch handover.

When you’re off watch it’s mostly about trying to sleep. With only 4 hours until you’re back on again, you’ll typically manage at best 3 and a quarter hours by the time you account for time to fall asleep and wake up, getting undressed and dressed, and performing minor ablutions.

For ocean passages, where the swell is such that normal cooking is pretty challenging, we try and have the majority of our lunches and dinners precooked and portioned individually in foil trays in the freezer. That way we can just sling them in the oven and 30 minutes later they’re ready.

And that’s it. 4 hours on, 4 hours off, eat, sleep, watch, rinse and repeat. For 7 or 8 days straight until we arrive at our next destination. Pretty boring stuff really.

But after the “excitement” of the first few days, we’ll gladly take boring anytime!