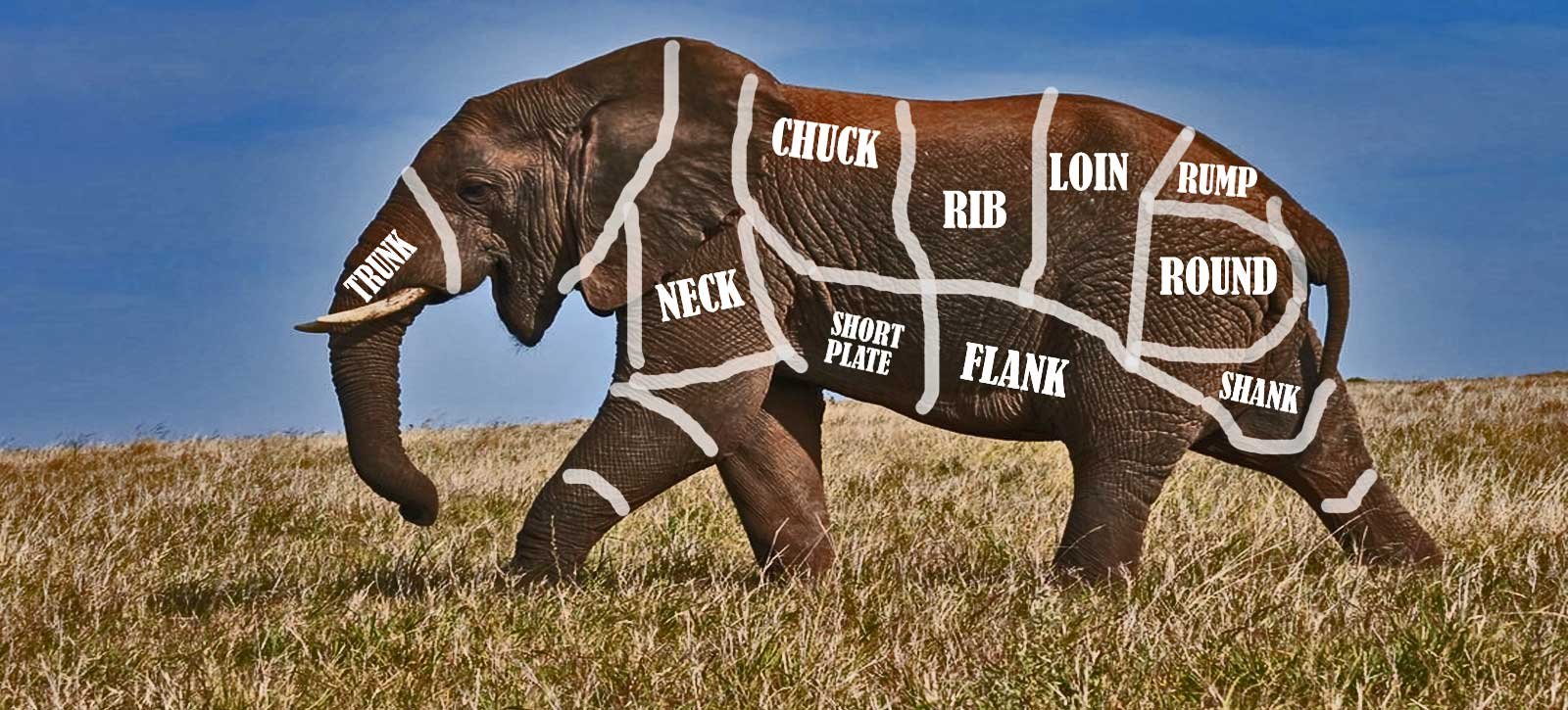

How do you eat an elephant?

Day 1 : Ascension Island to Azores

Friday, March 18th 2022

As well as being the longest passage we’ll make on our circumnavigation, this one also promises to be one of the most interesting from a strategy and planning perspective.

Since our first day has been a dream start, smooth downwind sailing with small waves and moderate winds, I thought I’d take you through our thinking for how we’re planning to eat this particular elephant.

We’ve broken the passage down into 5 easily definable bites, not just because psychologically it makes it easier to chew what we’ve bitten off, but also because the fact that we are travelling such a long distance across the planet from south to north means we’re going to be encountering very predictable, and quite dramatically changing, sailing conditions.

Our 5 phases are going to be:

Phase 1 – Ascension to the ITCZ (Approximately 7 days): Easy downwind sailing

Phase 2 – The ITCZ (approximately 5 days): No wind, with occasional violent squalls

Phase 3 – The Uphill Battle (approx. 15-20 days): Uncomfortable, upwind sailing

Phase 4 – The Azores High (approx. 2-3 days): No wind

Phase 5 – The Final Approach (3-5 days): Maybe big storms, maybe easy – impossible to know in advance

Most circumnavigations follow the “Trade Winds” from east to west, which give steady and reliable wind direction and strength. Overall, that’s what we’re doing too, but this diversion to Europe that we’re making sees us traverse the trade wind belts and encounter a few other weather phenomena that are worth explaining to give context to our strategy.

So first of all, what are these so called Trade Winds? They are caused by the rotation of the earth, and exist in a band between 5 degrees and 25 degrees south and north of the equator. South of the equator, they blow from the South East. And North of the Equator, they blow from the North East.

Sailors have been using the predictable nature of these winds for centuries to navigate the oceans.

In between these two zones, between 5 degrees South and 5 Degrees North, is the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone, also known as the ITCZ, or the doldrums. In this area, there is typically no wind at all, or very gentle breezes, punctuated by short-lived, 20-minute, violent squalls and thunderstorms.

For so long as one is heading from East to West, and you stay in the Trade Wind latitudes between the Tropics, the sailing is easy. If you wish to sail from West to East, you need to move to the higher latitudes south and north, where the wind direction reverses, but where it is also much stronger and stormier.

We’ve been in the southern trade wind zone since we left Namibia, which is why it’s been easy downwind sailing all the way. We’re currently at 7 degrees south, and heading North West, which is why our Phase 1 is so enjoyable,

Soon, though, we’ll be entering Phase 2 - the ITCZ, or Doldrums.

This area is also sometimes referred to as the Horse Latitudes. The story goes that large sailing ships were sometimes becalmed there for so long, they might resort to eating the horses on board to fend off starvation. Other versions of the same story say the horses were simply thrown overboard to save weight and allow the vessel to creep slowly towards the edge of the zone where the winds would resume.

Either way, we have engines, and no horses, so it doesn’t really apply to us (but Coco should be very nervous – that’s all I’m saying).

Annoyingly the ITCZ does not start and stop precisely at 5 degrees south and north respectively as I over-simplistically described above, but actually oscillates further south and north of the equator at different times of the year. It also gets narrower or wider depending on how far east or west one is.

At this time of year, the ITCZ in the Atlantic Ocean varies in size between 600 and 1,000 nautical miles. The further west we get, the narrow and shorter it is, the further east, the wider.

(you can see this phenomenon if you look at the blue area of no wind on the Predict Wind map behind this blog post).

We have a total motoring range of just over 1,000 miles, and since we will undoubtedly have to motor for large sections of the ITCZ, part of our plan is to cross it at it’s narrowest, which is why we’re heading NW from Ascension (this will also feed into a decision about the Cape Verde Islands, about which more later).

There will also be some light winds occasionally in the ITCZ, so from time to time we may elect to sail (very) slowly for a day or two to conserve fuel. And there will also be some short periods of strong winds a few times each day, where we will definitely be turning off the engine and sailing. These typically only last 20 minutes or so, and can be quite violent. But they do punctuate the monotony, help us save fuel, and since they’re often accompanied by rain, give the boat (and us) a vital and much need wash down and break from the intense heat and humidity.

Once we are clear of the ITCZ, the challenging part can begin.

We’re calling Phase 3 the “Uphill Battle”, and as you’ll see, it’s most definitely not going to be plain sailing.

Those SE trade winds which were so helpful south of the equator when we were heading North West, will become our enemy now that we’re into the North East Trade winds of the northern hemisphere and we need to head more or less due North. For over 1,500 miles.

At that point, we’re going to be close hauled, or sailing as close to the wind as physics and our tolerance for discomfort will allow.

For all her many virtues, Steely is not a particularly close-winded boat. What that means is that where some raceboats can sail at 30 or 40 degrees to the true wind, and a few “close-winded” cruising boats can sail at 40 or 50 degrees to the true wind, Steely (like most of her cruising peers) can only really manage around 60 degrees to the wind.

As we exit the ITCZ, the Azores will be around 2,000 miles due north of us. If we try to head straight for them, that means the NE Trade wind will mostly be coming at us at around 30 -45 degrees. In a race boat, we might be able to point directly at our destination, but in Steely, we’ll have to point 15-30 degrees to the west of the Azores, essentially continuing to sail just north of NW. Eventually, we’ll most likely have to tack and sail to the east to regain some ground. But agonisingly, since Steely sails at 60 degrees to the (true) wind, that means we tack through 120 degrees, and so instead of heading due east, we’ll actually be heading East South-East, giving up some of our hard-won miles of Northing.

This dance will continue for at least two weeks, and maybe three, during which time the winds will be mostly steady at 15-20 knots, but there will be occasional periods where they’ll build to 20-25 knots. In those periods, we’re definitely expecting the ride to be a bit rough – not too bad, but enough that we’ll be slowing Steely down and sailing for comfort, not speed.

As we get north of 25 degrees north, we will eventually find the trade winds run out, to be replaced by the Azores High – our Phase 4.

This massive windless area gets smaller and larger throughout the year, and also moves it’s position. But it’s always SW of the Azores, and its inevitable that we’ll sail into it.

If we’ve done a good job in Phase 2, we’ll have plenty of fuel left, and we can use it to motor out of the high at a strategic pace – strategic because of what awaits us in phase 5 – the final approach.

Once we are out of the Tropics and into the northern latitudes, the prevailing wind becomes westerly, but brings with it a series of depressions or areas of low pressure. These are typically accompanied by storms, which bedevil the North Atlantic all year round, but are worse in winter. We’ll be arriving in early spring, where there will still be enough storms that we will use our time in the Azores High to either drift slowly or motor hell-for-leather, to time our last few hundred miles into the Azores in reasonably pleasant (or at least not scary) weather.

Very few boats make this passage each year.

Last year, friends of ours on a boat called Anna Caroline (Hi Janneke and Wietze, if you’re reading this) made the passage in their own navy-hulled steel boat. They did so a month or two later than us, so their weather was just a little better. And I think their boat is a little closer-winded than Steely so they managed Phase 3 with no tacks at all, and then belted through Phase 4 to avoid a storm coming their way.

They managed the trip in 32 days, I believe – if we could make it in 37, I’ll be delighted.

Whichever way you look at it, it’s a serious undertaking, and more than a little daunting, if I’m being honest.

Now, a couple of friends (shout out to Brad and Paul) have asked if we considered stopping at the Cape Verde Islands, which are around half way between Ascension and Azores. The short answer is that we have considered it, and might well still actually do it, but there are some real downsides, as well as the plusses.

On the positive side of the ledger, it would make the trip psychologically easier, it would allow us to refuel (which could be important given how much we expect to burn crossing the ITCZ), it would give us a more favourable wind angle for the leg from the Cape Verdes to Azores, and it would allow us to actually pick a weather window for the final leg which would help us to potentially avoid those Phase 5 storms referred to above.

But it comes at a cost.

Once we are north of the ITCZ, the Cape Verdes will be directly upwind (not 30 or 40 degrees off the wind, as the Azores will be), so it would be a real slog to get there, involving lots of long tacks through 120 degrees, effectively adding a further 700-1,000 miles to the trip. If we set out now for the Cape Verdes, it would also make sense to cross the ITCZ much further East than we are currently planning, at it’s widest point, pushing the windless zone to close to a thousand miles – pretty much our entire range.

So we’d be 100% committed to stopping at the Cape Verdes to refuel, no matter how hard we were finding the upwind part – we just wouldn’t be able to bail out. Plus, with the extra miles, and allowing time for a stop in Mindelo, we’d be adding another 2 weeks at least to our overall schedule. Not to mention quite a lot of extra expense.

Instead, we’re hedging our bets. Once we are in Phase 3, and heading directly for the Azores, we’ll still have the ability to put a long tack in and head to the Cape Verdes if there are any problems on board, or if we see any issues ahead with the weather.

In the meantime though – we have a plan, and we’re going to eat this elephant one bite at a time.

Hope you all stay with us for the most interesting journey of our circumnavigation.

Day 1 Statistics:

Time on passage so far: 20 hours

Average Speed in last 24 hours: 5.2

Official Length of intended Route: 3,480 nm

Distance Sailed so Far: 108nm

Theoretical Distance to go: (3,480 – 108): 3,372

Actual Projected Distance to Go: 3,370

(so far so good, but I expect these numbers to diverge wildly once we get into Phase 3, which is why I’m going to track it. I expect we’ll sail closer to 4,500 miles)