Who the Hell is this Murphy, anyway?

Day 2: Inverness to London

Sat Aug 27 2022

It’s 11pm, two hours into my 9pm - 1am watch, and I can hardly believe what I’m seeing.

There’s wind!

A nice steady 10-12 knots, from about 30 degrees off our starboard side. It shouldn’t be happening – not according to the forecast anyway, which has been extremely accurate so far. When I first noticed it, an hour ago, I assumed it was just a fleeting gust, and normal service (less than 5 knots, on the nose) would resume momentarily.

So I flicked our Chart Plotter over to Wind plot mode, and spent much of the ensuing hour watching it like a hawk.

It’s not as if there was much else to do. We’re in the calm before the (navigational) storm right now. The intensity of the tidal narrows during our departure from Inverness has long been left behind. And the maelstrom of gas platforms, oil rigs, wind farms and sand banks don’t start until we reach the coast of East Anglia, still more than 24 hours away.

For the entire last 24 hours, then, there’s been virtually no action at all. There was one wind farm that we passed – so new, it wasn’t on the chart yet. I spotted the first turbine when it was about 25 miles away, just a tall white line against the horizon, and thought it was a sail boat. Then, fleetingly, I thought I must be sailing into a race, when more and more “sailboats” appeared.

Finally, about 15 miles out, I worked out what I was looking at. We shifted course to skirt the edges, but as we motored onwards, more and more appeared over the horizon, and we had to keep dialling a few more degrees to port into the autopilot. Finally, we reached the edge of the enormous array, and passed by less than half a mile away. There were over a hundred of them, stunningly beautiful, stark and utterly motionless in the brilliant sunshine, against the blue sky and the glassy calm waters.

But that was it, the only excitement for the day.

Actually, I tell a lie. There was a 10-minute period during my watch earlier in the afternoon when I saw two puffins, four giant seals, and four lobster pots. Literally the only things I saw in the water all day. It wasn’t a coincidence that they all came together like a cluster of buses when you’ve been waiting for an hour at the bus stop, of course. There was a navigational buoy nearby, and it must have been acting as a Fish Attraction Device, so all the sealife was clustering in the vicinity.

Anyway, I digress. The point is, that staring at the wind plot graph was at least giving me something to do.

As the hour wore on and the wind did not revert to the mean as expected, I began to feel the first twinges of an emotion that is no stranger to me.

A low, barely perceptible adrenaline surge as my subconscious starts to register the possibility of something good happening. The first signs of Optimism rearing its head and setting off to battle with its world-weary foe, better known as Bitter Experience.

After an hour of watching the graph, which is hardly moving at all (a nice steady 10-12 knots, which is more like 15 knots of apparent wind as it’s from in front of us), my inner monologue is becoming impossible to ignore.

It’s screaming at me.

“This is crazy. Why are we motoring when we could be sailing at the same speed. Why did you even buy a sail boat anyway, if you’re going to motor when there’s perfectly good wind. WE SHOULD BE SAILING!”

I’m lying of course. It’s not a monologue at all. It’s very much a dialogue, and the voice of Bitter Experience is fighting back.

“It’s 11pm. You’re tired. It’s going to take 10 minutes to get the sails out. You’ll need to go out to the poop deck to move the traveller, and you shouldn’t be leaving the cockpit at night without waking up Jen. Talking of which, the noise of the electric winches is going to wake up Jen, which is not really fair. And talking of noise, once the sails are up and the engines are off, the noise of the autopilot directly under Jen’s ear is going to driver her mad.”

Optimism isn’t having any of it, of course. “Seriously, is that the best you can do? These are just excuses. If you listened to any of that, you’d never put the sails up at all. Besides, we’ve been motoring for a solid 36 hours now. Don’t you think the engines would like a break? And never mind the engines. What about you? Wouldn’t you enjoy the peace and quiet? The feeling of the boat leaning its shoulder over just slightly and accelerating in the puffs of breeze? The gurgle of water gently rushing past the hull. Isn’t that what you’re HERE FOR???”

With solid arguments like that, there can be only one outcome. At least in MY psyche. Optimism wins.

With one last stare at the wind graph, almost willing the numbers to fall, Bitter Experience gives up, folds its arms, and goes to sit sulkily in the corner.

I go down below, switch on the deck lights, and grab a head torch. I unzip the port side of the cockpit enclosure. I need to pop out and move the jib car backwards, and also nip back to the poop deck to move the traveller car for the mizzen just past the centre line.

Our rules on this are quite clear. No leaving the cockpit after dark without the other person in the cockpit, and I should be tethered on. I consider my options. The rules are quite sensible, of course, but these are extraordinarily benign conditions. It’s hard to conceive of how I could fall overboard in these flat waters, with only a light to moderate wind, with Steely’s high solid life rail and bulwarks, especially given I’m only moving 6 feet forwards and 12 feet back from the cockpit to perform my two tasks.

There’s no way I’m waking Jen up for that.

Technically I should at least put on my lifejacket and clip on my harness and tether, but the 2 minutes of pfaffing seems ridiculous for the 30 seconds I’ll be out of the cockpit.

I decide to hell with the rules.

Very carefully, I step outside the cockpit and slide the jib car traveller back a few feet. Then even more carefully, I move to the aft deck and slide the mizzen traveller to what will be the “high side”. All the while I keep my centre of gravity low, well below the solid life rails, and even sit down on the poop deck to slide the traveller. It’s pretty unnecessary in these conditions, but at least it salves my guilty conscience somewhat.

When I return to the cockpit, I check the wind graph again – it’s still showing steady wind strength and direction.

I need to turn 10 degrees to port to give us an apparent wind angle of 40 degrees, which is the closest that Steely can sail to the wind. That puts us a little off course, but the trade-off is more than worth it get some sailing in, and since we’re turning to seaward and there’s no navigational hazards nearby, there’s no real downside other than a few extra miles to be sailed.

I pull the mizzen sail out and set it. It takes all of 20 seconds – it’s such an awesome and easy sail to work with.

The Genoa is a different story, of course. It’s massive, bigger than our other 3 sails put together, and while it’s not at all difficult to deploy single handed, it does take time to set the lines up to run freely, and needs to be pulled out slowly and steadily to keep it under control.

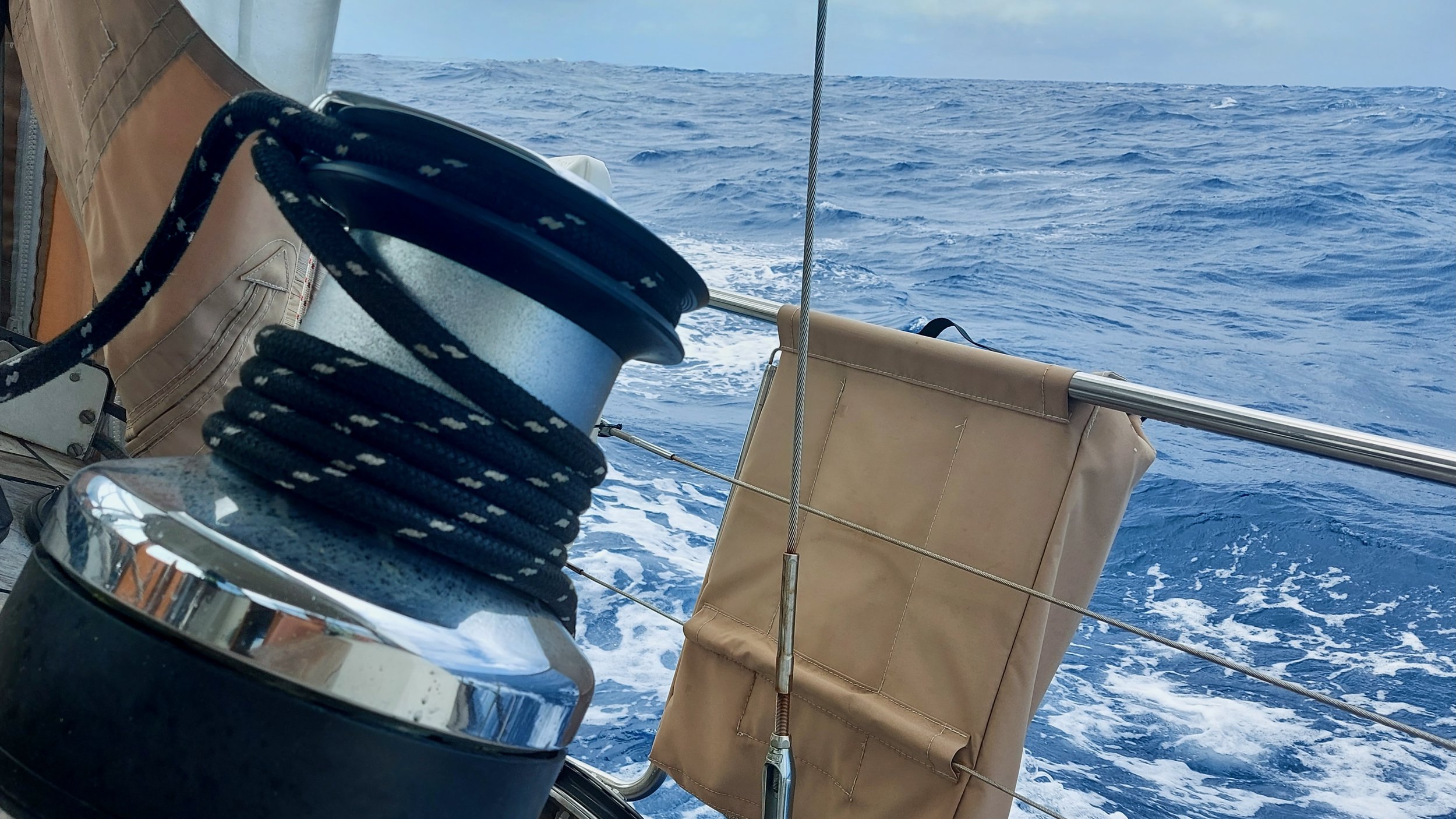

I knock the engine revs back to idle and pull out the genoa. Once it’s fully out and trimmed correctly, I stop and watch for a few seconds as our speed settles down.

Exactly as expected. We were motoring at 5.7 knots previously, and we’re now sailing at 5.4 knots – that’s definitely acceptable. I briefly consider pulling the mainsail out also, which would have us sailing at more like 6.5 to 7 knots, but decide it’s more hassle than it’s worth, especially at this time of night.

I turn off the engine and decklights.

Ah, bliss. The sweet sound of silence.

Well, not quite silence of course. There’s also the beautiful sound of water gurgling gently against the hull, like Steely talking to us to tell us how happy she is.

And she’s not the only one who’s happy. Coco suddenly appears in the cockpit, and miaows excitedly to tell me how happy she is that the engine is off. She’s such a good sailing kitty.

I set the autopilot to wind vane mode, so it will hold us at a constant angle to the wind, which saves me the effort of continuously trimming the sails as the wind oscillates backwards and forwards.

I pop back downstairs and creep into the aft cabin to see if Jen has awoken with all the kerfuffle.

Paradoxically, it’s much easier to sleep when the engines are on than when they’re off. The solid drone of the engines is essentially white noise, drowning out all the other creaks, thuds, winch noises and splashes which are much more intermittent and random, and thus more likely to keep (or wake) you up.

It also drowns out the noise of our backup autopilot that is mounted directly behind the headboard of our bed. Since our primary is on the blink at the moment, we’ve been happily using our backup, but with the engine off, I feared it might be disturbing Jen.

The good news is that Jen is snoring softly, seemingly unaware of the autopilot.

I return to the cockpit, resume my watchkeeping position, and relax.

But this is not our first rodeo, my friends. And you and I know perfectly well what’s going to happen next.

It only takes 10 minutes, or about one mile. But slowly, and inevitably, the wind direction starts to shift, causing us to veer further and further off course. And at the same time, the wind speed slowly starts to drop. Another 10 minutes later and we’re now 40 degrees off course, and sailing at just 3.5 knots. And just as I start to contemplate putting everything away again and switching on the engine, I hear Jen go into the bathroom.

And with that, I know the gig’s up. Whether my shenanigans had woken her up, or her going to the loo would have happened anyway., one thing is for sure. There’s absolutely no way she’s going to be able to go back to sleep in the aft cabin with the whirr of the autopilot.

She’ll need to decamp to our Pullman cabin, which is already set up for this very purpose. So it’s nota big deal really, except for the fact that we’re now sailing in the wrong direction. Slowly.

Nope, there’s nothing for it – engine on and sails away.

As I switch the engine back on, Bitter Experience looks on smugly, and doesn’t say a word.

He doesn’t need to.

We all know that I should know better by now.

The only way that wind was going to stay constant was if I’d kept on motoring. That’s just the way the world works. Murphy wouldn’t have it any other way.

Day 2 Statistics:

Total Time on passage: 1 day, 22 hours

Total Distance covered: 275 nm

Distance in last 24 hours: 143

Average Speed: 6.0 knots

Max Speed: 8.2 knots

Number of miles sailed vs motored in last 24 hours: 2 vs 141